After The Shutter: My Entire 35mm Workflow Exposed

A behind-the-scenes look at how I scan, archive, and organize decades of 35mm film using a Plustek 8300 AI, Lightroom, and a self-built home lab.

If you shoot film, you already know the truth: the moment you finish a roll, you’ve only done half the work. Today I'm going to share my entire workflow for after the shutter goes off.

I send my 35mm rolls to a local lab to be developed (Shoutout to San Marcos Film Lab) — uncut, unscanned. From there, it’s all me: I scan, archive, and edit every frame by hand. It’s a slower, more deliberate way to work, but it keeps me connected to the photograph.

The Scan Is the Second Capture

My scanner is a Plustek OpticFilm 8300 AI, paired with SilverFast 9. It’s built for high-resolution 35mm film work — 7200 dpi optical and excellent tonal range.

At this stage I am not interested in automation or mass imports; I purposely scan each individual frame. I spend time with the image throughout the process, which is an import part of curating my work. I adjust every exposure and color balance myself in SilverFast 9 — the same way I would in the darkroom, by instinct and by eye. It’s slow, meditative, and deeply satisfying.

Everything lands on my NAS, with high resolution scans often exceeding 300MB. To manage this scale and volume, I built a home server and Network Attached Storage to support my workflow and archival process. To ensure all of my images are stored redundantly in the case of a drive failure, I run my NAS on four 4TB Seagate IronWolf drives in RAID 5 — redundant, reliable, and quietly humming away.

For further redundancy, I keep a second copy of key images and a web-sized archive on an external hard drive. If the house burns down, we're ready to go.

Photo Organization Begins During The Initial Scan

I have a folder in my NAS directory for each Camera body I own. Each roll name starts with the film stock and ends with the subject. That path alone tells me what I need — camera, film, and story.

Once the scans are saved, I move into Lightroom. My edits are minimal: crop, straighten, spot clean, sharpen for web, and fine-tune color.

I make color adjustments the same way I used to in the darkroom: gently, until it feels right. The goal isn’t to “improve” the photo. It’s to let the film’s character speak clearly.

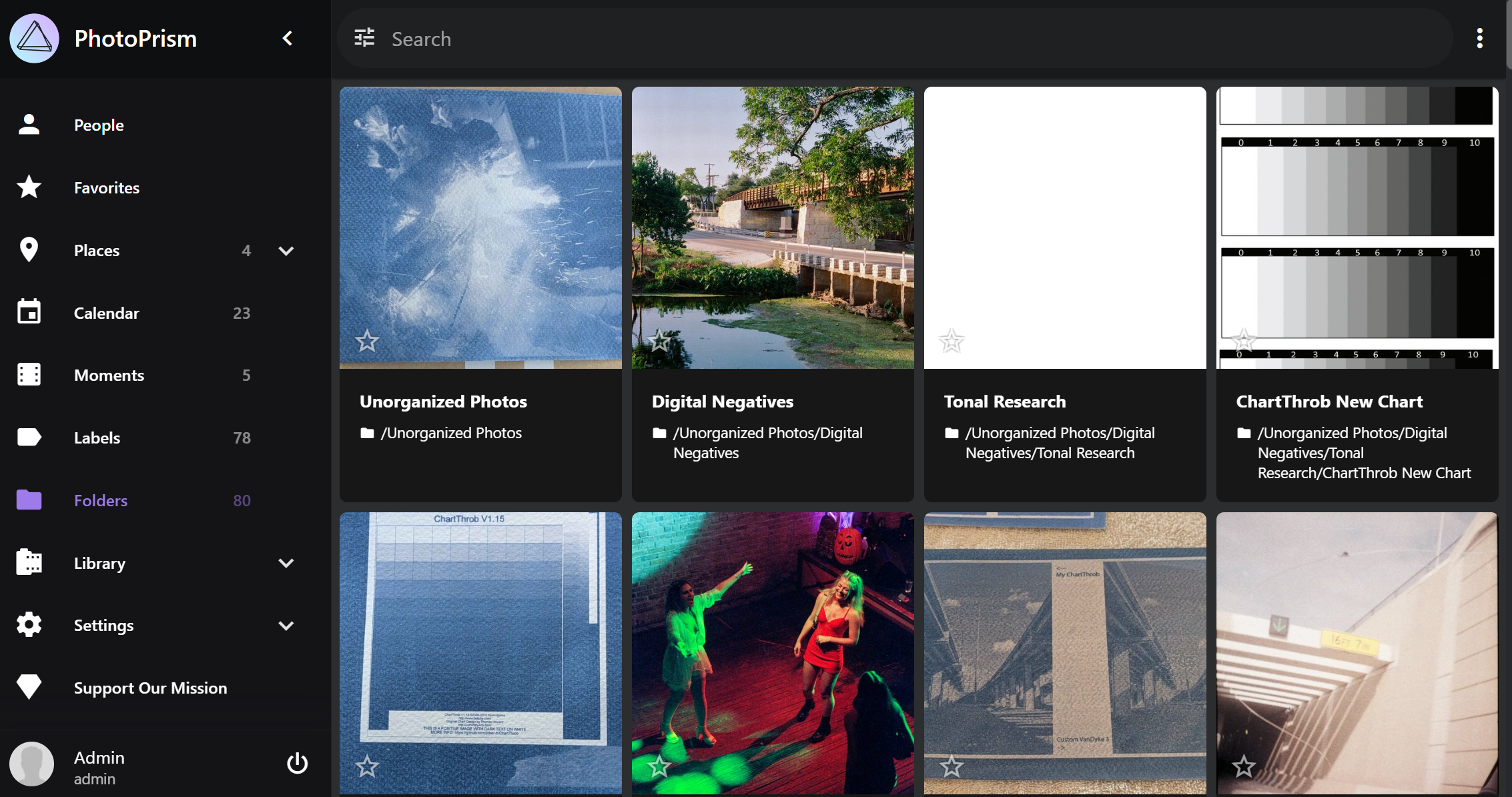

PhotoPrism: Free, Open Source Photo Organizing Software

With thousands of large images my archive would often lag or freeze within traditional organizing tools like Lightroom. I use PhotoPrism — an open-source photo manager that runs on my home lab as a Docker container in Proxmox. This is entirely free - no subscription fee or hosting costs, with features that include:

- AI Assisted Object Detection, Scene & Face Recognition

- Indexes Metadata and integrates existing Lightroom tags

- Duplicate detection & Clusters similar images

- Fast search & filtering

- Web UI Preview can quickly load images for your review

- Private, Self Hosted, Free

- Directly Mounts my NAS to automatically access my entire personal media archive.

While this article is not intended to function as a review, I would heartily recommend PhotoPrism to other enthusiasts. The only con I have experienced to date is the automatic object assistance is less than perfect, and some amount of custom tagging will help the search function best. Personally, I usually complete this as part of my Lightroom workflow.

Why I Still Do It All Myself

Archiving isn’t just logistics — it’s philosophy. This system exists so I can make sense of my own history: thousands of negatives, two decades of film, each frame a small act of attention. When you make an image, it's a fraction of a second (generally). Scanning, processing, organizing, and archiving is a way of respecting that moment, and spending even more time with it. It helps me connect to my work and identify which shots are good, and which are just noise.

Interested in learning more about setting up your own? Drop me a comment, I'd love to chat.